SENTENCING OR A MEDICAL PROCEDURE – BOTH ARE EQUALLY STRESSFUL. FOR A SUCCESSFUL OUTCOME, PREPARATION FOR BOTH IS CRUCIAL.

Marc Blatstein was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he attended high school. He later attended George Washington University in Washington, DC., for his undergraduate degree, where he received a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. He worked a job on the side to help offset the high costs of a college education.

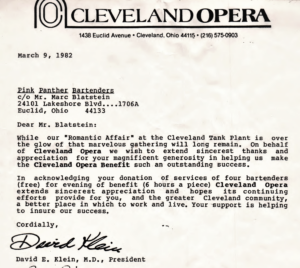

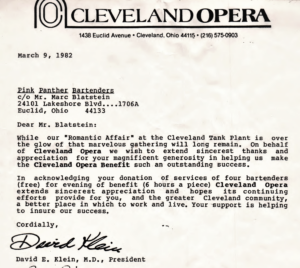

Marc later attended Ohio College of Podiatric Medicine, where he studied medical training and obtained his Doctor of Podiatric Medicine Degree.  While studying there, he started the “Pink Panther Bartenders” along with his brother and two of his classmates to help with some of the costs of higher education. At one point, he was grateful to be asked to participate in a Gala for the Cleveland Opera, to which he agreed.

While studying there, he started the “Pink Panther Bartenders” along with his brother and two of his classmates to help with some of the costs of higher education. At one point, he was grateful to be asked to participate in a Gala for the Cleveland Opera, to which he agreed.

He then attended a surgical residency covering Podiatric Medicine and Surgery, followed by a 31+ year career as a single practitioner. While in practice, Marc Blatstein incorporated a medically oriented shoe store, wound care, and physical therapy programs into his practice.

HOBBIES

Most of my joys have been spent on the water, while I have enjoyed power and sailing with my 1st mate, Bailey.

In the end, though, the peace of sailing is where I have spent most of my time.

In the end, though, the peace of sailing is where I have spent most of my time.

EDUCATION | PRACTICE AND CONSULTING TIMELINE

George Washington Univ., BA in Psych. (’77),

Externship(s):

• Lutheran Hospital Baltimore, MD. (’82),

• Atlanta Hospital & Medical Center, Atlanta, GA (’82).

Ohio College of Podiatric Medicine, Doctor of Podiatric Medicine, DPM (’83),

Lawndale Community Hospital Surgical Residency in Podiatric Medicine & Surgery (’84)

Foot And Ankle Medicine and Surgery, 1985 – 2023 Physician Physician Presentence Report Service, LLC., 2011 – Current

PRIVATE PRACTICE 1985 – 2023

POPULAR COMPONENTS OF MY PRACTICE

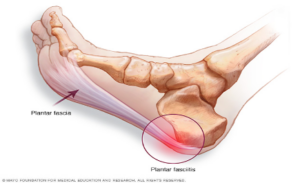

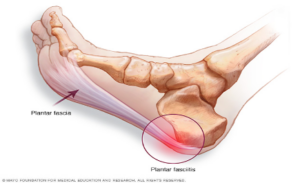

I. PLANTAR FASCITIS

According to Dr. Marc Blatstein, morning heel pain is the most common complaint he treats. Patients relate that it is pain upon  standing first thing in the morning. While the pain initially is excruciating, with ambulating, the pain may subside, only to come back again with a vengeance after sitting and then immediately returning after standing up again.

standing first thing in the morning. While the pain initially is excruciating, with ambulating, the pain may subside, only to come back again with a vengeance after sitting and then immediately returning after standing up again.

The plantar fascia is a ligament attached at one end to the bottom of the heel (in a medial, central, and lateral band), then fanning out into the ball of the foot, thus acting as a shock absorber for the foot. As the foot impacts the ground, the plantar fascia stretches slightly with each step. When these excessive pressures of pulling the plantar fascia on the heel occur over time, with an innocent step (like stepping on a marble or off a curb), they create small tears in the plantar fascia (the ligament on the bottom of the foot) resulting in a small amount of bleeding, pain & inflammation. Medical literature initially thought heel pain was due to a bone spur on the bottom of the heel bone (or calcaneus). We now know that the pain is due to excessive tension on the plantar fascia as it pulls on its attachment to the inside/medial aspect of the calcaneus (heel) bone.

In diagnosing heel pain, Dr. Marc Blatstein relates that over the years, patient care has demonstrated that not all bone spurs are painful, and everyone with heel pain (or plantar fascitis) does not necessarily have to have bone spurs. A complete history and physical exam play a significant role in approaching this diagnosis, along with weight-bearing X-rays, which help determine if a heel spur is present (fractured) or associated with other pathologies contributing to the diagnosis.

Initially, treatment by Dr. Marc Blatstein can start with a combination of one or all of the following:  padding & taping of the foot in a supportive nature, taking oral anti-inflammatory medications, immobilization of the foot in a walking cast, physical therapy as well as implementing specific stretching exercises. Should additional treatment be necessary, cortisone injections and orthopedic functional foot orthotics may be prescribed. Should any or all of these treatments fail, and after a detailed review of X-rays and lab results with your physician, surgical intervention may be considered, and according to Dr. Marc Blatstein, it is very effective. Here, an Endoscopic Plantar Fasciotomy is one (of many) of the procedures that could be recommended. A plan is formed between you and your doctor for a successful outcome meant to add a full and enjoyable life to your years.

padding & taping of the foot in a supportive nature, taking oral anti-inflammatory medications, immobilization of the foot in a walking cast, physical therapy as well as implementing specific stretching exercises. Should additional treatment be necessary, cortisone injections and orthopedic functional foot orthotics may be prescribed. Should any or all of these treatments fail, and after a detailed review of X-rays and lab results with your physician, surgical intervention may be considered, and according to Dr. Marc Blatstein, it is very effective. Here, an Endoscopic Plantar Fasciotomy is one (of many) of the procedures that could be recommended. A plan is formed between you and your doctor for a successful outcome meant to add a full and enjoyable life to your years.

II. THE CIRCULATOR BOOT™

A significant part of Dr. Blatstein’s practice is using The Circulator Boot™ as a method of treatment that helps with the core elements of lower extremity wound therapy: bacterial control, increased blood supply, moisture, and the removal of dead or damaged tissues to help the healing of healthy tissue. Along with other modes of treatment, surgical debridement of infected wounds, the use of antibiotic medications along with home care, and boot therapy in Marc Blatstein’s eyes may improve the blood supply and control the infection when standard methods of treatment are failing.

The Circulator Boot™(Mayo Clinic.org), from Dr. Marc Blatstein’s years of experience, the end-diastolic timing of its leg compressions (this FDA-approved non-invasive technology) provides benefits in preventing leg amputation. Poor circulation and infection are the leading causes of 90,000 diabetic amputations that occur every year in the United States.

The Circulator Boot™, “A leg with poor arterial blood flow, may be likened to a dirty sponge that is half wet. Squeezing such a sponge disseminates the water throughout the sponge. Soaking and repeatedly wringing the water from the sponge may help clean it. In like fashion, the heart monitor of the Circulator Boot™ is timed to allow each arterial pulse wave to enter the leg as best it can (to partially wet the leg “sponge”). Boot compressions provide a driving force to disseminate blood around the leg and, at the same time, press venous blood and excess tissue water from the leg. Patients with an 80 beats per minute pulse rate might receive 4800 compressions an hour. Patients with severe arterial leg disease might receive 100 such treatments or close to a half-million compressions! Breakdown of the clot, re-channelization of blocked vessels, and forming small new vessels may help restore blood flow.”

This may be an option for those who may be facing amputation. Dr. Marc Blatstein recommends learning more about The Circulator Boot™ as a Treatment method via The Circulatory Boot Service at the Mayo Clinic.

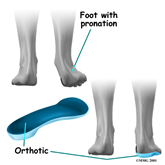

III. TARSALTUNNEL SYNDROME

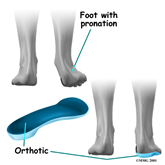

Similar to Carpal Tunnel, Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome is due to the compression of a nerve called the Posterior Tibial Nerve. Dr. Marc Blatstein, a Podiatric Surgeon, explained that Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome occurs over time as the nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in symptoms such as burning, electric shocks, and tingling, as well as a shooting type of pain. Other factors that Dr. Marc Blatstein has found factors contributing to Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome come from either an overly pronated foot, which puts a stretch on the nerve, pressure on the nerve from soft tissue masses such as ganglions, fibromas, or lipomas that physically compress the nerve, as well as other insults to the nerve.

the Posterior Tibial Nerve. Dr. Marc Blatstein, a Podiatric Surgeon, explained that Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome occurs over time as the nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in symptoms such as burning, electric shocks, and tingling, as well as a shooting type of pain. Other factors that Dr. Marc Blatstein has found factors contributing to Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome come from either an overly pronated foot, which puts a stretch on the nerve, pressure on the nerve from soft tissue masses such as ganglions, fibromas, or lipomas that physically compress the nerve, as well as other insults to the nerve.

The diagnosis is usually quickly made by physical exam and the patient’s complaint history. Observation may reveal a slight swelling just on the inside of the ankle joint. As part of the physical exam, Dr. Marc Blatstein finds that gently tapping the inside of the ankle joint in the acute phase will result in a tingling sensation that may shoot up the leg and/or into the foot. Nerve conduction studies are another tool that will reveal if there is damage to the nerve.

Treatment of the Tarsal Tunnel involves many different components, some of which are correcting the  abnormal pronation of the foot [which is accomplished with prescription functional foot orthotics]. Along with this, oral anti-inflammatory medications, vitamin B supplements, &/or steroids may provide some benefit but are rarely curative. Should a soft tissue mass compress the nerve, surgical removal of the mass may be necessary. Surgical correction of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome has a good chance of success; at the same time, the overpronation of the foot still needs to be followed with functional foot orthotics.

abnormal pronation of the foot [which is accomplished with prescription functional foot orthotics]. Along with this, oral anti-inflammatory medications, vitamin B supplements, &/or steroids may provide some benefit but are rarely curative. Should a soft tissue mass compress the nerve, surgical removal of the mass may be necessary. Surgical correction of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome has a good chance of success; at the same time, the overpronation of the foot still needs to be followed with functional foot orthotics.

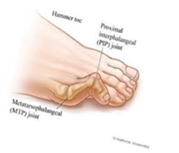

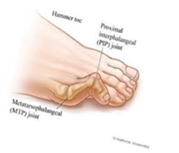

IV. THE PAINFUL HAMMERTOE

According to Dr. Marc Blatstein, hammertoes appear with the toes bent in a clawing fashion. Hammertoes may be flexible or rigid; flexible infers that you can manually straighten the toes, while it is impossible to straighten the rigid toe without surgery. Because most of us wear enclosed shoe gear, the pressure caused by the shoe gear we wear causes the toes to become painful. On top of this, pressure forms hard corn, while on the bottom of the foot, the toe pushes the metatarsal bone down, forming a callus under the metatarsal head. Treatment of hammertoes can be approached in many ways. Dr. Marc Blatstein recommends a combination of appropriate shoe gear and a functional orthotic prescribed as a shoe insert to help the hammertoes from progressing or worsening. In the very initial stages, while the toe is still flexible, it can

impossible to straighten the rigid toe without surgery. Because most of us wear enclosed shoe gear, the pressure caused by the shoe gear we wear causes the toes to become painful. On top of this, pressure forms hard corn, while on the bottom of the foot, the toe pushes the metatarsal bone down, forming a callus under the metatarsal head. Treatment of hammertoes can be approached in many ways. Dr. Marc Blatstein recommends a combination of appropriate shoe gear and a functional orthotic prescribed as a shoe insert to help the hammertoes from progressing or worsening. In the very initial stages, while the toe is still flexible, it can  be tapped into its corrected position, utilizing a functional orthotic. This conservative treatment also consists of hammertoe and buttress pads, all available over the counter, and open-toe shoes.

be tapped into its corrected position, utilizing a functional orthotic. This conservative treatment also consists of hammertoe and buttress pads, all available over the counter, and open-toe shoes.

With continued pain, correction of the deformity, while successful, depends on whether they are rigid or flexible. While the hammertoe is still flexible, a simple tendon release followed by taping it in the corrected position is usually adequate. Then, a functional orthotic may be prescribed to help maintain this correction. With a rigid hammertoe, the surgical procedure consists of removing some skin and a small section of bone. Dr. Marc Blatstein told us that in cases of a severe hammertoe deformity, a pin may be used to hold the toe in its corrected position for several weeks & then it is removed. Following your surgeon’s after-surgery instructions is essential in all cases to get the best result.

V. INGROWN TOENAIL

Victoria Azaranka recently dropped out of a tennis match because of an ingrown toenail. Dr. Marc Blatstein tells us how to prevent ingrown toenails. Several people wait far too long to have the procedure, and they have more complications.

Most people do not think an ingrown toenail will get in the way of their profession, but it did for one person. Victoria Azaranka, the world’s No. 1 tennis player, was sidelined due to an ingrown toenail in her right big toe. The toenail had become ingrown and made it so painful she had to sit out of a match against Serena Williams, a former world’s No. 1 women’s tennis player. The cause behind the ingrown toenail is a surprise, a bad pedicure.

PUBLICATIONS:

Nails Magazine, Contributor, through the 1990s

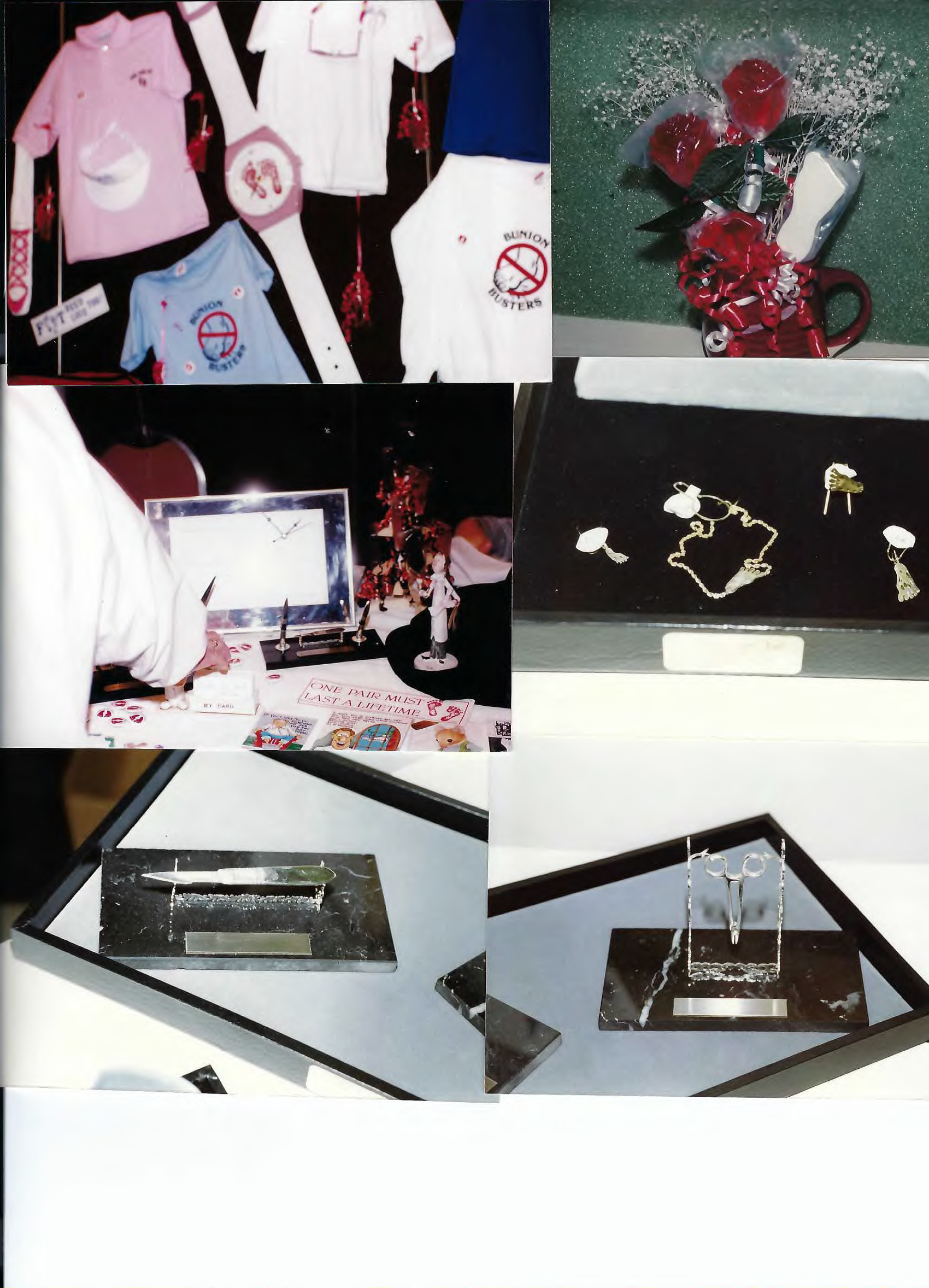

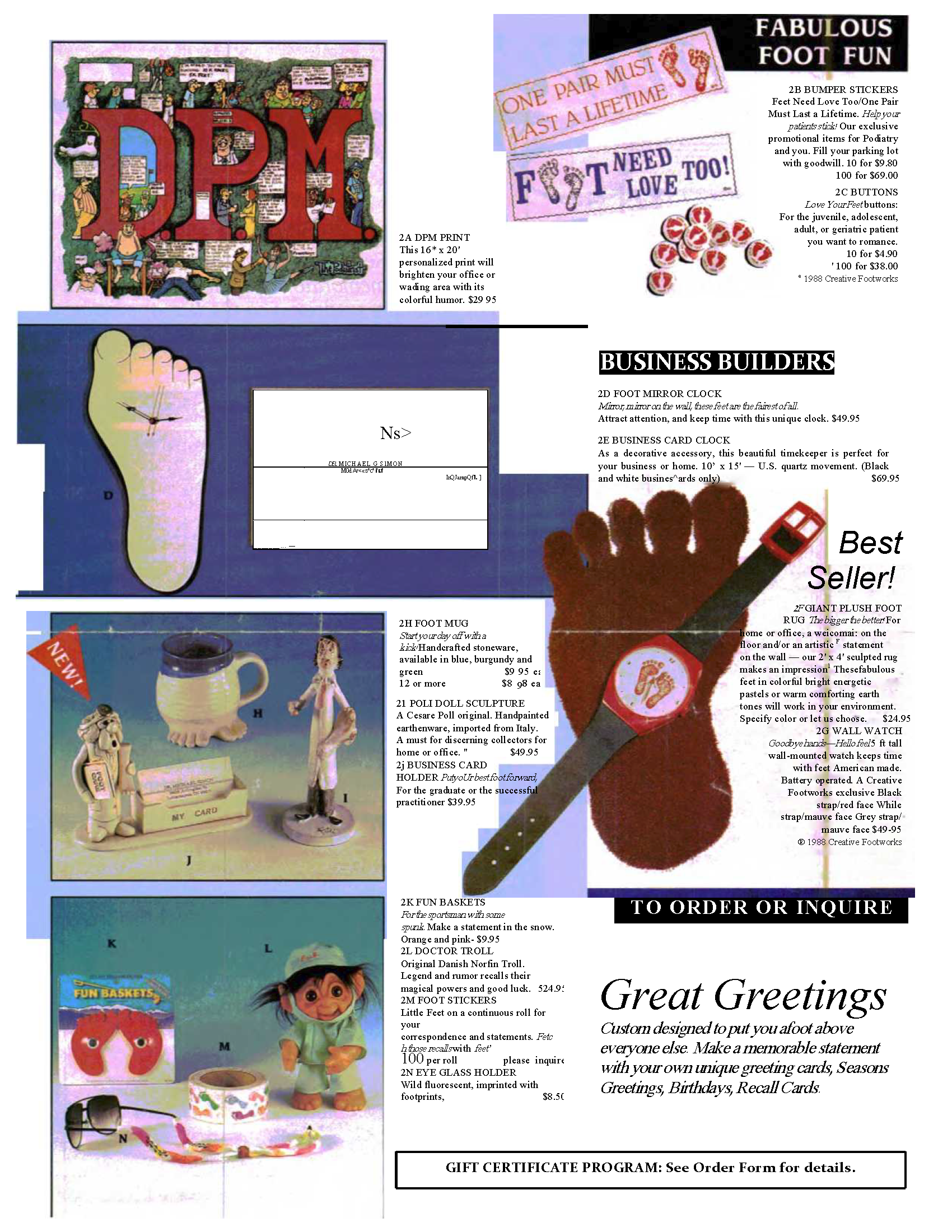

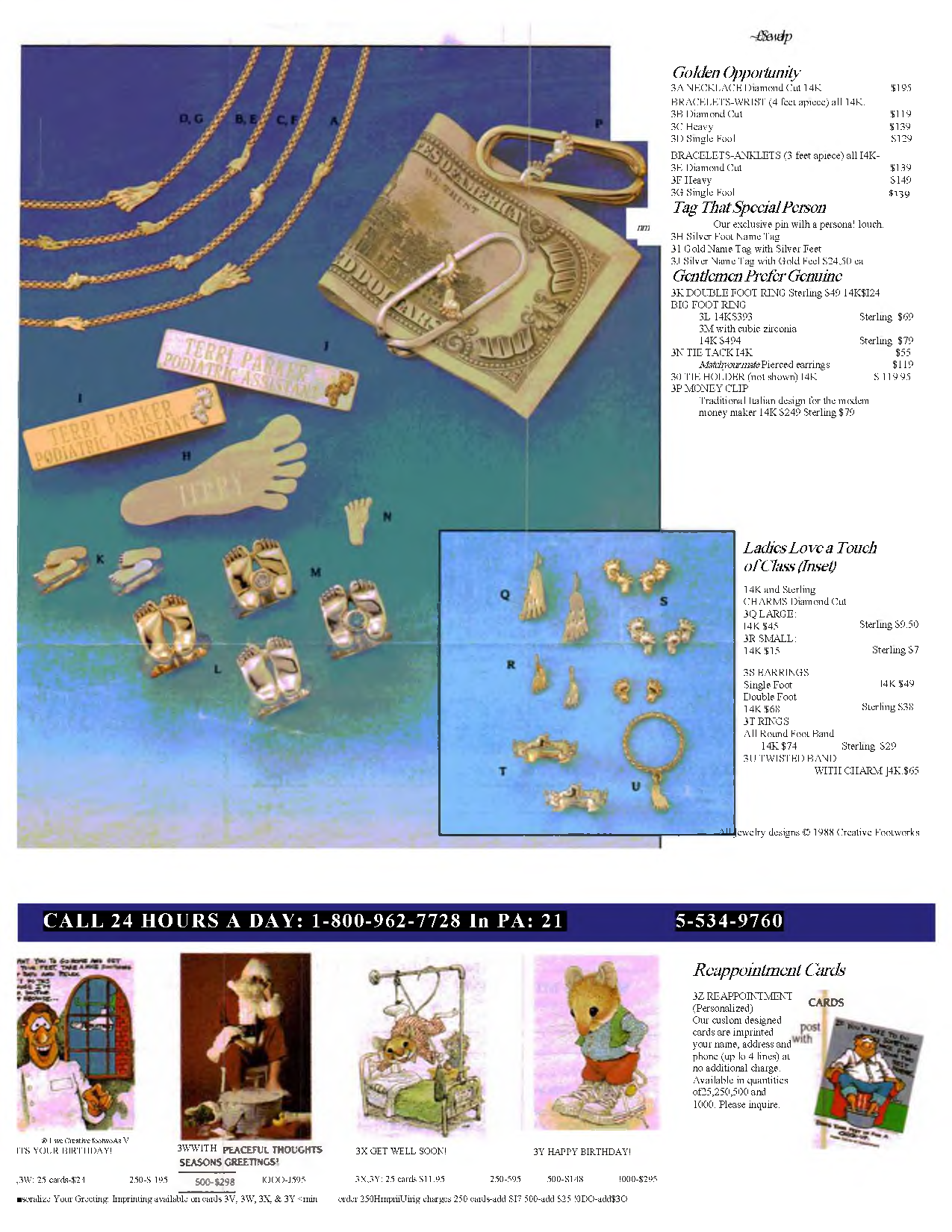

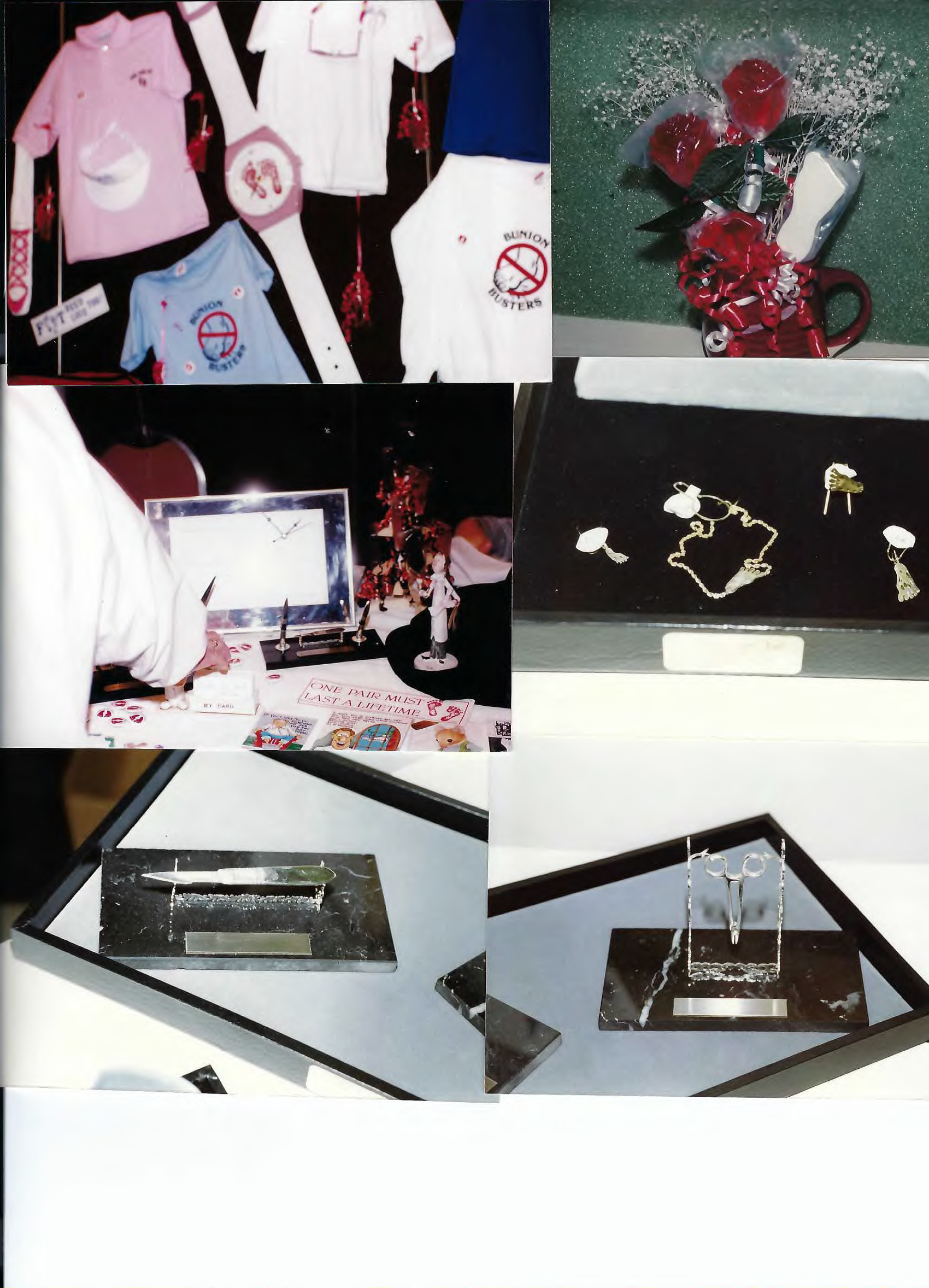

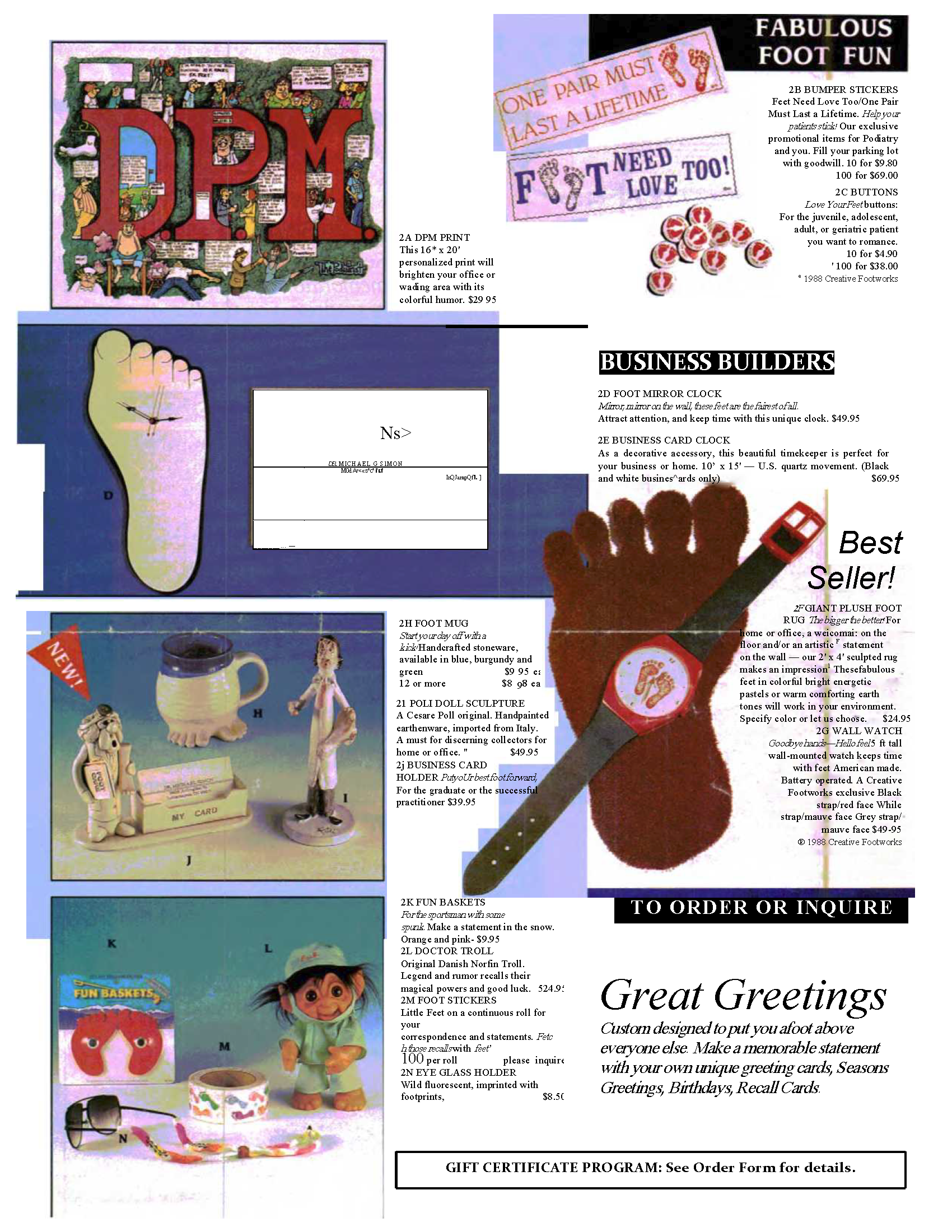

CREATIVE FOOTWORKS

Novelties, Business Supplies, and Gifts for those practicing Foot and Ankle Medicine and Surgery, 1986-1996.

PHYSICIAN PRESENTENCE REPORT SERVICE, LLC. 2011 – Current

PUBLICATIONS:

The Federal Lawyer, Co-authored, 2021

American Bar Association, Co-authored two Chapters in 2022

While studying there, he started the “Pink Panther Bartenders” along with his brother and two of his classmates to help with some of the costs of higher education. At one point, he was grateful to be asked to participate in a Gala for the Cleveland Opera, to which he agreed.

While studying there, he started the “Pink Panther Bartenders” along with his brother and two of his classmates to help with some of the costs of higher education. At one point, he was grateful to be asked to participate in a Gala for the Cleveland Opera, to which he agreed.

In the end, though, the peace of sailing is where I have spent most of my time.

In the end, though, the peace of sailing is where I have spent most of my time.

standing first thing in the morning. While the pain initially is excruciating, with ambulating, the pain may subside, only to come back again with a vengeance after sitting and then immediately returning after standing up again.

standing first thing in the morning. While the pain initially is excruciating, with ambulating, the pain may subside, only to come back again with a vengeance after sitting and then immediately returning after standing up again. padding & taping of the foot in a supportive nature, taking oral anti-inflammatory medications, immobilization of the foot in a walking cast, physical therapy as well as implementing specific stretching exercises. Should additional treatment be necessary, cortisone injections and orthopedic functional foot orthotics may be prescribed. Should any or all of these treatments fail, and after a detailed review of X-rays and lab results with your physician, surgical intervention may be considered, and according to Dr. Marc Blatstein, it is very effective. Here, an Endoscopic Plantar Fasciotomy is one (of many) of the procedures that could be recommended. A plan is formed between you and your doctor for a successful outcome meant to add a full and enjoyable life to your years.

padding & taping of the foot in a supportive nature, taking oral anti-inflammatory medications, immobilization of the foot in a walking cast, physical therapy as well as implementing specific stretching exercises. Should additional treatment be necessary, cortisone injections and orthopedic functional foot orthotics may be prescribed. Should any or all of these treatments fail, and after a detailed review of X-rays and lab results with your physician, surgical intervention may be considered, and according to Dr. Marc Blatstein, it is very effective. Here, an Endoscopic Plantar Fasciotomy is one (of many) of the procedures that could be recommended. A plan is formed between you and your doctor for a successful outcome meant to add a full and enjoyable life to your years.

the Posterior Tibial Nerve. Dr. Marc Blatstein, a Podiatric Surgeon, explained that Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome occurs over time as the nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in symptoms such as burning, electric shocks, and tingling, as well as a shooting type of pain. Other factors that Dr. Marc Blatstein has found factors contributing to Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome come from either an overly pronated foot, which puts a stretch on the nerve, pressure on the nerve from soft tissue masses such as ganglions, fibromas, or lipomas that physically compress the nerve, as well as other insults to the nerve.

the Posterior Tibial Nerve. Dr. Marc Blatstein, a Podiatric Surgeon, explained that Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome occurs over time as the nerve becomes inflamed, resulting in symptoms such as burning, electric shocks, and tingling, as well as a shooting type of pain. Other factors that Dr. Marc Blatstein has found factors contributing to Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome come from either an overly pronated foot, which puts a stretch on the nerve, pressure on the nerve from soft tissue masses such as ganglions, fibromas, or lipomas that physically compress the nerve, as well as other insults to the nerve. abnormal pronation of the foot [which is accomplished with prescription functional foot orthotics]. Along with this, oral anti-inflammatory medications, vitamin B supplements, &/or steroids may provide some benefit but are rarely curative. Should a soft tissue mass compress the nerve, surgical removal of the mass may be necessary. Surgical correction of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome has a good chance of success; at the same time, the overpronation of the foot still needs to be followed with functional foot orthotics.

abnormal pronation of the foot [which is accomplished with prescription functional foot orthotics]. Along with this, oral anti-inflammatory medications, vitamin B supplements, &/or steroids may provide some benefit but are rarely curative. Should a soft tissue mass compress the nerve, surgical removal of the mass may be necessary. Surgical correction of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome has a good chance of success; at the same time, the overpronation of the foot still needs to be followed with functional foot orthotics. impossible to straighten the rigid toe without surgery. Because most of us wear enclosed shoe gear, the pressure caused by the shoe gear we wear causes the toes to become painful. On top of this, pressure forms hard corn, while on the bottom of the foot, the toe pushes the metatarsal bone down, forming a callus under the metatarsal head. Treatment of hammertoes can be approached in many ways. Dr. Marc Blatstein recommends a combination of appropriate shoe gear and a functional orthotic prescribed as a shoe insert to help the hammertoes from progressing or worsening. In the very initial stages, while the toe is still flexible, it can

impossible to straighten the rigid toe without surgery. Because most of us wear enclosed shoe gear, the pressure caused by the shoe gear we wear causes the toes to become painful. On top of this, pressure forms hard corn, while on the bottom of the foot, the toe pushes the metatarsal bone down, forming a callus under the metatarsal head. Treatment of hammertoes can be approached in many ways. Dr. Marc Blatstein recommends a combination of appropriate shoe gear and a functional orthotic prescribed as a shoe insert to help the hammertoes from progressing or worsening. In the very initial stages, while the toe is still flexible, it can  be tapped into its corrected position, utilizing a functional orthotic. This conservative treatment also consists of hammertoe and buttress pads, all available over the counter, and open-toe shoes.

be tapped into its corrected position, utilizing a functional orthotic. This conservative treatment also consists of hammertoe and buttress pads, all available over the counter, and open-toe shoes.