The information in this series and on PPRSUS.com (and PPRSUS Resources) is readily accessible and completely Free to all. Should you wish to engage my services, my contact information is at the end.

Welcome to my video series, ” INDICTED AND FACING PRISON.” My name is Marc Blatstein, and I know firsthand how surreal and overwhelming this experience can be. That’s why I’m here to provide you with crucial daily information. With Knowledge and Preparation, you can navigate these challenging times with Confidence.

The DOJ and Feds have been asking questions; their case is mostly complete. With a 98% conviction rate, the odds are not in your favor. However, knowledge is power, and it’s in your hands. Delaying your next step could have severe consequences.

Your future is at stake, so hiring a legal team with a proven track record of successfully defending cases like yours is critical. Don’t just settle for experience; choose a team that is a good fit and can get you the best outcome. Make the right choices today, and you can move forward with confidence tomorrow.

Minimum security institutions known as Camps have dormitory housing, a relatively low staff-to-inmate ratio, and limited or no perimeter fencing. These institutions are work- and program-oriented, and many are located adjacent to larger institutions or on military bases, where inmates help serve the labor needs of the larger institution or base.

This video compares BOP Federal Prison Camps (FPC) to Satellite Camps attached to higher-security facilities. Brief Overview: Satellite Camps usually have more FSA programs, while FPCs may have less stress overall as the guards do not have to deal with the adjacent higher-security facility and don’t need to rotate between the two.

There are two types of Minimum Camps.

· Federal Prison Camps (FPC): These are free-standing with limited fencing and more freedom of movement.

· Satellite Camps: These are associated with higher security institutions. Many BOP institutions have a small, minimum-security camp adjacent to the main facility. These camps, often called Satellite Prison Camps (SPC), provide inmate labor to the main institution and off-site work programs. FCI Memphis has a non-adjacent camp that serves similar needs.

Low-security Federal Correctional Institutions (FCI) have double-fenced perimeters, mostly dormitory or cubicle housing, and strong work and program components. The staff-to-inmate ratio in these institutions is higher than in minimum-security facilities.

Medium-security FCIs (and USPs designated to house medium-security inmates) have strengthened perimeters (often double fences with electronic detection systems), mostly cell-type housing, a wide variety of work and treatment programs, an even higher staff-to-inmate ratio than low-security FCIs, and even greater internal controls.

High-security institutions, also known as United States Penitentiaries (USP), have highly secured perimeters (featuring walls or reinforced fences), multiple- and single-occupant cell housing, the highest staff-to-inmate ratio, and close control of inmate movement.

Correctional Complexes: Several BOP institutions belong to Federal Correctional Complexes (FCC). At FCC, institutions with different missions and security levels are located in close proximity to one another. FCC increases efficiency by sharing services, enables staff to gain experience at institutions of many security levels, and enhances emergency preparedness by having additional resources within close proximity.

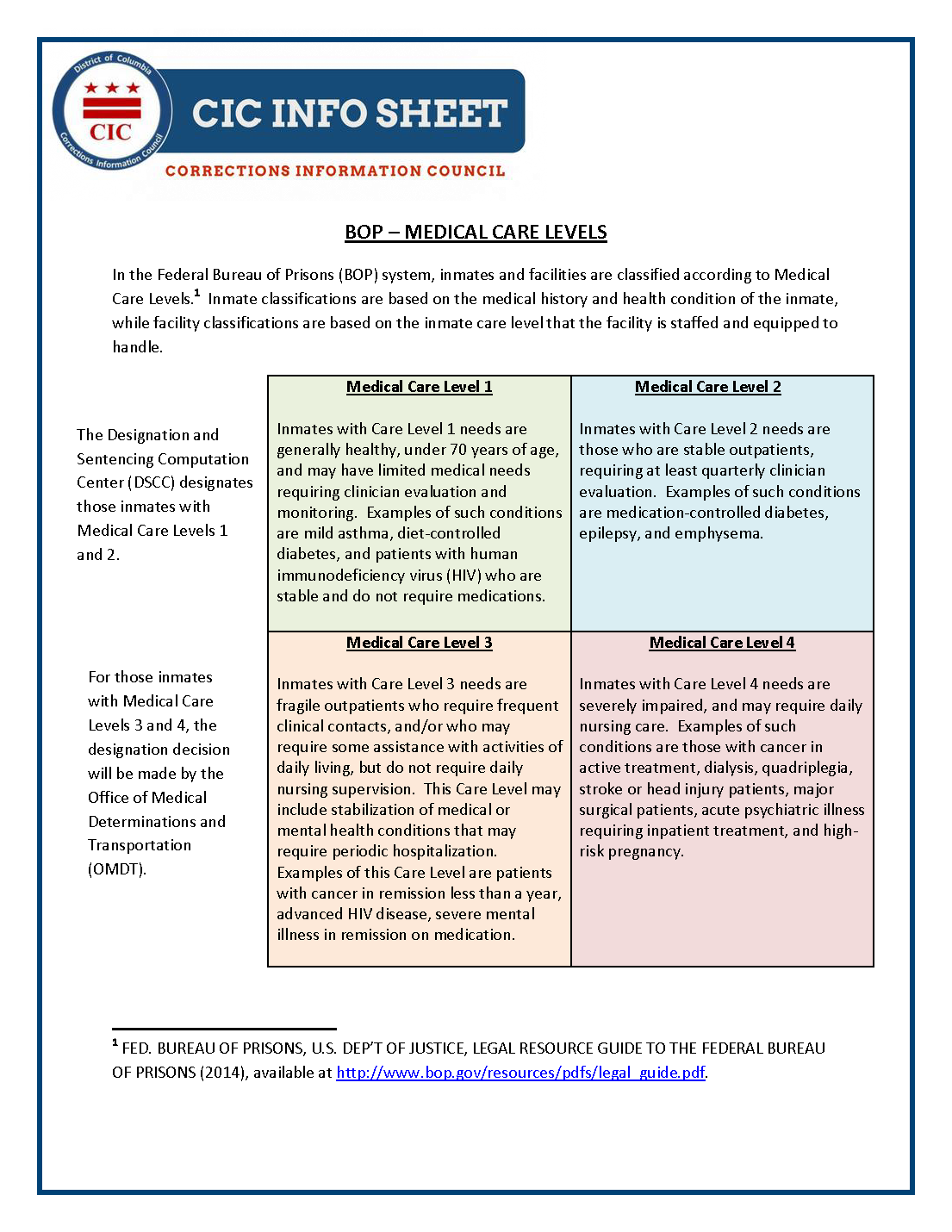

Administrative facilities are institutions with special missions, such as the detention of pretrial offenders, the treatment of inmates with serious or chronic medical problems, or the containment of extremely dangerous, violent, or escape-prone inmates. Administrative facilities include:

Metropolitan Correctional Centers (MCC),

Metropolitan Detention Centers (MDC),

Federal Detention Centers (FDC), and

Federal Medical Centers (FMC):

- Carswell FMC,

- Devens FMC,

- Fort Worth FMC,

- Lexington FMC,

- Rochester FMC,

Federal Transfer Center (FTC), the

Medical Center for Federal Prisoners (MCFP) and the

Administrative-Maximum (ADX) U.S. Penitentiary.

Except for the ADX, administrative facilities can hold inmates in all security categories.

Federal Satellite Low Security: FCI Elkton and FCI Jesup each have a small Federal Satellite Low Security (FSL) facility adjacent to the main institution. FCI La Tuna has a low-security facility affiliated with, but not adjacent to, the main institution.

Secure Female Facility: Currently, the BOP has one Secure Female Facility (SFF) unit (located at USP Hazelton, WV) designed to house female inmates. Programming at the SFF promotes personal growth by addressing the unique needs of this population.

To engage my services or to have your concerns answered, Call me Today: 240.888.7778. This is my Cell and I personally answer and return all calls. You can also get additional information on my website @: PPRSUS.com.